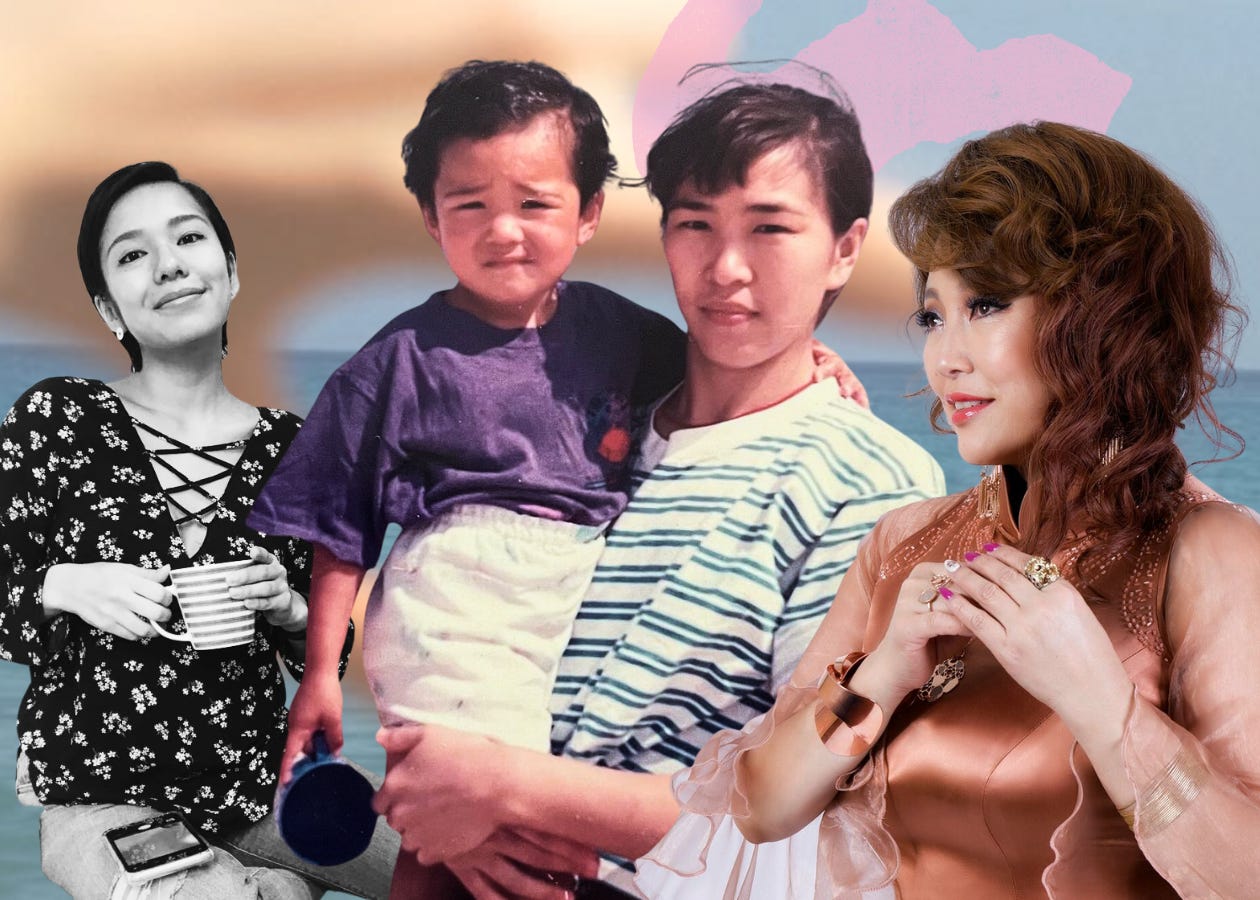

Mongolia's queen of pop Sarantuya and the healing power of her music

A story about intercultural parenting, reconciling unspoken discord, and finding common ground through music

The first time that I ever heard the spellbinding voice of Mongolia’s pop icon, Sarantuya, was when I was just a kid living with my mother in Mexico City. The song was “Duuchin Chamdaa” (rough trans. Beloved Singer) and it had just been released. The year was 1998, I was seven, and the rest of my life had just begun.

Thousands of miles from her native country of Mongolia, her family, and anyone who looked like her, my mother would crank up Sarantuya’s cassette every Saturday morning while she cleaned. I understood enough Mongolian to understand requests and commands around the house, but understanding lyrics was beyond my seven year old self. Plus, my Spanish was just getting good again so the song might as well have been gibberish. Little did I know that this song was to become the anthem of the untainted love I had for my mother and the unspoken pain of the culture gap that always preceded it.

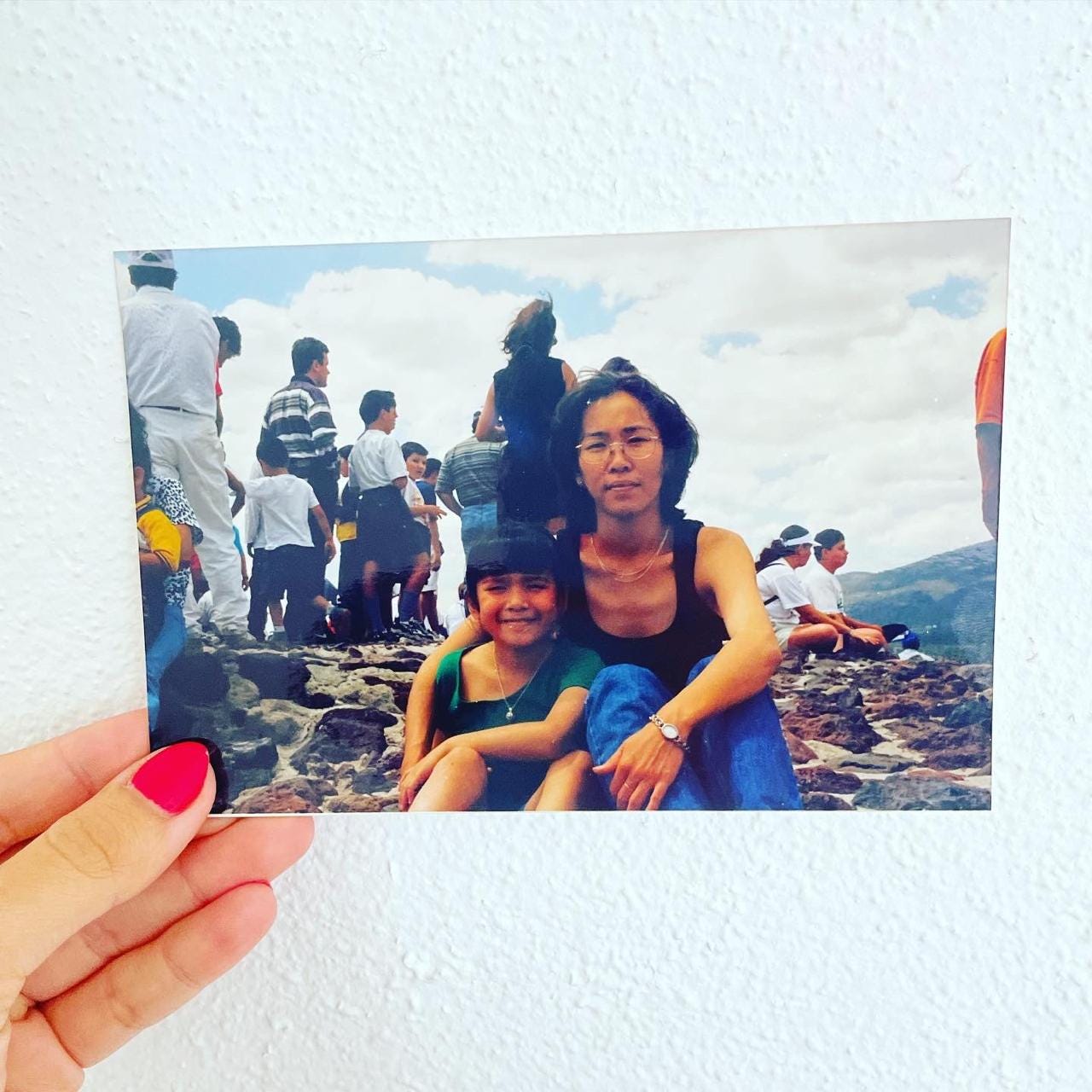

In retrospect, I can only imagine that all those Saturdays ago, she was simply homesick. By 1998, she’d been living in Mexico for nearly four years—which doesn’t sound like a lot if you have a strong community (ie. Chinatown, Koreatown, Expat Town, etc) but back then mom was one of just a handful of Asians in Mexico City that didn’t even know each other. She did have a paisana, my friend Ricardo’s mother, in town and I like to imagine that they were each other’s consolation during periods of homesickness. In fact, I know they were. I was there. Save her friend, my mother immersed herself into Mexican culture as fully and completely as she could and only indulged in Mongolian food and music at home.

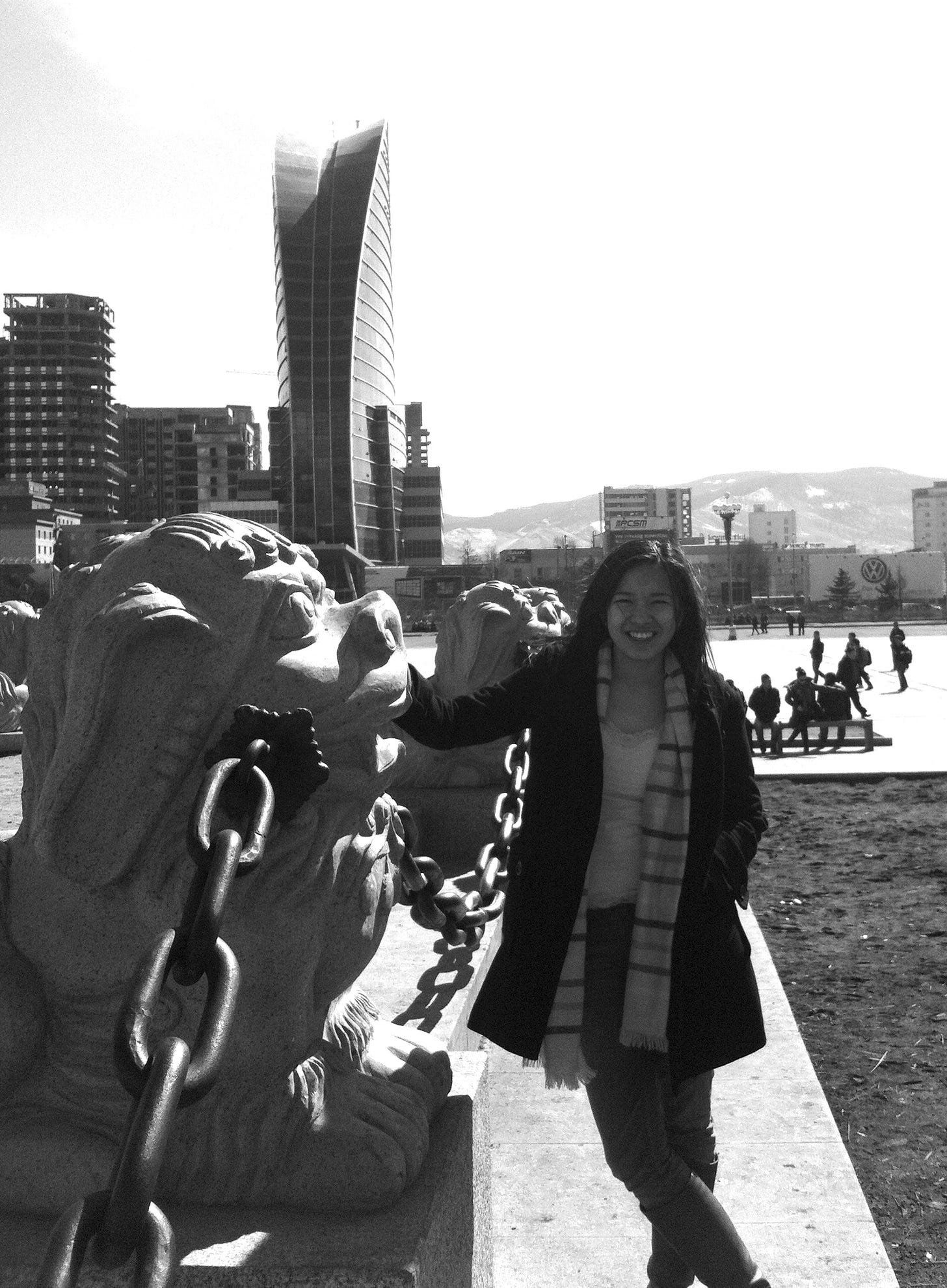

For perspective, as I type these words, I have already been living in Mexico for 4 years with little to no Mongolian friends and I have to admit that even I, who wasn’t born nor raised in Mongolia, find myself missing the melodically uvular sound of the language and the sharp wit so unique to its distinct fricative hisses. If this is how I feel as a half-Mexican, half-Mongolian who was raised in the US for most of her life, then of course my mother, who was born and raised in Mongolia for most of her life, missed the distinct sound of her native language. It sounds strange, but sometimes I wish I could go back in time and befriend my 28 year old mother as an adult and enjoy the cassette together over a cup of tea. I wasn’t so mature at 7, I guess.

Singing off key

Having been left under the care of several relatives both in Mexico and Mongolia up until 1997, I admit that finally living with my mother was a little disorienting if awkward. Even at my young age, I think I could sense her shame for leaving me those first years. Her penance was palpable even to me. (Now that I am older than she was back then, I understand that it must have been disorienting for her, too. She was a kid herself and her life as a full-time single mother had just begun.) Even though she’d only left me to get back on her feet, those precious years were lost and set us up for a relationship that was disjointed, cacophonous, and jarring… and we were about to play catch up for the foreseeable future. She remained an exotic enigma to me for years.

And these days, the more I listen to the song “Duuchin Chamdaa”, the more I find myself asking “How was my mother feeling at that/this age? Was she lonely? Was she happy?” Oftentimes these questions have surprised me during the most mundane moments of my days in Australia, China, France, and Mexico where I began to understand what it was like to be the “exotic enigma” myself.

And since I was growing up as a Mexican kid, and later an American kid, I confounded my mother as well. The “West”, Mexico and the US, was wholly different than the Communist Mongolia she’d grown up in. As the years wore on, we tried unsuccessfully to see eye to eye making worse with each attempt. We were both taunted by the fear that we were worlds apart, irreparably off-key. Growing ever more frustrated with our deteriorating relationship, I became resolute at learning Mongolian for the sole purpose of knowing the side of myself that made me hers and made her mine hoping that somehow I could made the gap between us less glaring, less gaping, less gory.

“Growing ever more frustrated with our deteriorating relationship, I became resolute at learning Mongolian for the sole purpose of knowing the side of myself that made me hers and made her mine hoping that somehow I could made the gap between us less glaring, less gaping, less gory.”

Чамд баярлаж явдгийг хэн ч мэдэхгүй

Chamd bayarlaj yavdgiig hen ch medehgui

No one knows that I cherish you

Чамаас олигтойг нь би мэдэхгүй ээ

Chamaaas oligtoig ni bi medehgui ee

I don’t know anyone better than you

Чин зүрхэндээ дуулдгийг чинь хэн ч мэдэхгүй

Chin zvrkhendee duuldgiig chin hen ch medehgui

No one knows that I sing for you deep in my heart

Чамайг яасныг чинь хэн ч мэдэхгүй

Chamaig yaasniig chin hen ch medehgui

No one knows where you’ve gone

About Mongolia and the Queen of Pop

Sandwiched between Russia and China, Mongolia was a satellite state of the USSR until 1991. My mother was one of the many generations of children to went to Russian school and grew up speaking Russian and Mongolian in tandem. I suppose it wasn’t so farfetched that the kids who went to Russian school would want to go to “Mother Russia” after graduating, which is exactly what my mother did. She met my father in Moscow in the late 80s and I was born in 1991 right at the dusk of Perestroika and Glasnost and the dawn of a new epoch that was exciting, scary, traumatizing, and full of promise for all those who got to experience it.

Language wise, the Mongolian language has its roots in Altaic languages, like Turkish, though linguists consider this debatable. To my ears, though, Mongolian is a language that sounds similar to German and Arabic but with the poetry of Mongolian skies and mountains embedded in it. I swear you can hear the whispers of Mongolian winds in the lispy Ls and its mountains’ indomitable spirits in the guttural Gs.

“The West has Celine Dion. Mongolia has Sarantuya.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Mongolia began a new era of reclaiming her cultural identity after nearly seven decades of foreign influence that barred any expression of Mongolian national identity. With the influx of foreign media that had also previously been banned during the communist era, Mongolia of the 90s was suddenly a bird that was caged no more with a newfound creative power to harness. With it, flourished with a new era of pop, hip-hop, rap, poetry, sub-cultures and countercultures, and… just art in general. Sarantuya was one such singer whose ravishing voice blended Mongolia’s folk classics with new modern pop sounds, captivating the hearts of a new Mongolia.

“Sarantuya’s music is deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of Mongolians precisely because her music held their hand at the dawn of this new age.”

Sarantuya’s music is deeply embedded in the collective consciousness of Mongolians precisely because her music held their hand at the dawn of this new age. Her spellbinding voice, her arresting beauty, and her longstanding career cements her as pop superstar. You’d be stumped to find a Mongolian who doesn’t know Sarantuya and her songs. The West has Celine Dion. Mongolia has Sarantuya.

Singing in harmony

Over the years, my Mongolian improved and by the time I was 20 I could carry a conversation without inserting English words after every sentence. Consequently, Sarantuya’s “Duuchin Chamdaa” was no longer gibberish as it was when I was 7. Not only could I understand the words, but I could feel them too, and suddenly, I could feel my mother’s heart when she was 27 cleaning our apartment all those Saturday mornings. And the more Mongolian I learned, the more I spoke, the more I heard, so the more entrenched this song became in my marrow. If like the song, my mother was once a foreign concept that I struggled to understand, then now I could trace her every emotion in Mongolian and go as far as to emote it myself to the point of retrospectively sobbing and rejoicing with her the way I couldn’t all those years ago.

Sometimes I wonder if our mercurial relationship ever had anything to do with culture, language, and ethnicity. Maybe it was just the specific flavor of our mother-daughter relationship, but a mother-daughter relationship like any other. What I have learned so far is that to love is to see; to communicate is to risk miscommunicating— but you keep trying anyway. Even if you fail, hopefully you see (read: love) the person as they are and simply accept them. Throughout it all, Sarantuya’s “Duuchin Chamdaa” has soften the rougher edges around our relationship like ebbing water eroding the rougher edges of a rock. Her evocative voice overwhelms my heart with the pride that comes from knowing how to speak Mongolian and being able to emote, sing, and cry in its specific shades and hues… and for that, I am eternally grateful to my mother.

“Sarantuya’s evocative voice overwhelms my heart with the pride that comes from knowing how to speak Mongolian and being able to emote, sing, and cry in its specific shades and hues… and for that, I am eternally grateful to my mother.”

Энэ дууг ганцхан чи дуулж чаднаа

Ene duug gantskhan chi duulj chadnaa

You’re the only one who can sing this songЭнэ дууг ганцхан чи амьдруулна

Ene duug gantskhan chi amidruulna

You’re the only one who can bring this song to lifeИтгэж байна дуучин чамдаа

Itgej baina duuchin chamdaa

I believe in you, beloved singerЭхнээс нь дуулъя хоёулаа

Ehnees ni duuliya hoyulaa

Let’s sing it together from the top